Simple math behind major bison blunder

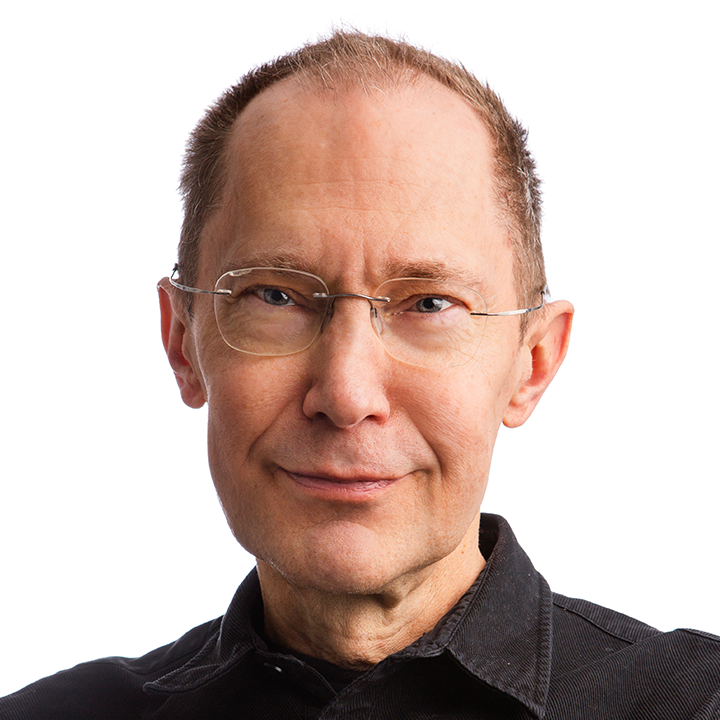

Environmental activists must become better at scrutinizing science, says F&F’s Per Snaprud after asking questions that led the WWF to withdraw a study.

Forskning & Framsteg’s Per Snaprud was able to reveal that the The Guardian’s article about Romanian bison as climate saviors was completely off the wall. Now the officials explain what went wrong.

Image: Getty images

The comment in Swedish: Dundertabbe bakom pinsam miss om visenter

I meet four embarrassed faces in a video meeting. Two of them are researchers at the highly ranked Yale University in the USA, and two represent the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in the Netherlands. They are here to explain what went wrong.

The background is an article in The Guardian. The British newspaper reported sensational results from a scientific study of European bison in Romania. A herd of 170 animals in the Țarcu Mountains was said to sequester as much carbon dioxide in the soil as the annual emissions from 1.88 million gasoline-powered cars.

”Too good to be true”

An extraordinary claim. A single bison would thus be able to offset the carbon emissions of 11,059 cars. This was based on research done by the Yale researchers on my screen, and funded by the WWF representatives.

When I obtained the report, I sent it to several Swedish experts. They commented the calculations with phrases like ”completely off”, ”too good to be true”, and ”wrong by a factor of one hundred”. So, I published a text questioning The Guardian’s talk about bison as climate heroes.

A few hours later, an email arrived from the press officer of the WWF in the Netherlands, who backtracked. She wrote that the news was being withdrawn ”due to calculations that are incorrect”.

”Embarrasing mistake”

But what exactly went wrong? I ask the most prominent researcher on my screen, Oswald Schmitz, professor of Population and Community Ecology at Yale University. He explains that they had a figure for the soil’s carbon dioxide uptake per square kilometer. That figure was supposed to be multiplied by the number of square kilometers the bison grazed on. Simple math. Unfortunately, the researchers multiplied once too many times. A mistake at elementary school level.

“Yes, it’s embarrassing,” says Oswald Schmitz.

New calculations led to the realization that the number of cars the bison can offset is only just over 2 percent of what The Guardian reported to its readers. Nearly 98 percent of the effect disappeared. And Oswald Schmitz says it was Forskning & Framsteg that made him realize his mistake:

“The questions you sent me, based on your experts’ feedback, made us look at the calculations again.”

The Guardian corrected its article. In an email to Forskning & Framsteg the newspaper’s environment editor explained that another department was responsible for the decision to publish this particular article. I can imagine that the heads of the various departments had a lot to say to each other.

Missed the peer review

An important aspect of the story is the fact that the scientific study behind all of it was unpublished. The project was a collaboration between several organizations: The WWF in the Netherlands, Rewilding Europe, Global Rewilding Alliance, and Yale School of Environment. None of the parties involved thought to submit the manuscript to a scientific journal for peer review before going to the world press. Such a review would very likely have prevented the blunder.

It is especially embarrassing that The Guardian swallowed the flawed calculations hook, line, and sinker. The newspaper maintains a high profile in its climate coverage. The climate crisis even has a special tab in the newspaper’s electronic news reporting. But in this case critical scrutiny was obviously lacking.

In the end, it’s very simple. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. If the evidence is lacking, it’s better to remain silent than to spread confusion.

Kunskap baserad på vetenskap

Prenumerera på Forskning & Framsteg!

Inlogg på fof.se • Tidning • Arkiv med tidigare nummer