Bild: Josefin Herolf

”Scientists Portrayed as Mass Murderers”

A heated debate is raging in the field of consciousness research. The science journalist Per Snaprud was present when two key figures in the conflict met to talk.

For a Swedish version, read here.

Outside an underground lecture hall at Tokyo University a crowd is bustling. Neuroscientists, psychologists, physicists, computer scientists and other experts have gathered here to discuss consciousness – the elusive inner perspective of mental life. The annual meeting is organized by the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC). This year’s event in June 2024 has drawn over 700 participants.

In the crowd, Liad Mudrik is talking to Hakwan Lau. I spot them by chance and intrude. It’s the first time they’ve met face-to-face since it all began exactly one year ago.

Photo: Tel Aviv University

– I sought you out here because I don’t like leaving things unsaid, says Liad Mudrik, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Tel Aviv University in Israel.

Photo: RIKEN CBS

– I’m happy to talk with you for a while, says Hakwan Lau.

Originally from Hong Kong, he now leads the Laboratory for Consciousness at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science, northwest of Tokyo.

I had expected to be asked to leave and let them talk in private. They have a lot to discuss – sensitive matters – and both know that I am a journalist. But neither object. Perhaps it’s because I was present the night in New York a year ago that sparked the dispute.

The Philosopher Won the Bet

It was June 23, 2023, Midsummer’s Eve in Sweden. In New York, the ASSC conference was underway. On that day, researchers and the public were invited to a gala evening. Over 600 people were seated in the Skirball Theater on downtown Manhattan. I sat in the spotlight on stage with philosopher David Chalmers and neuroscientist Christof Koch. Everyone was cheerful.

The two friends were there to settle a 25-year-old bet. During a pub crawl in Bremen in 1998, Christof Koch had wagered a case of fine wine that someone would discover what he called the neural correlate of consciousness – a simple process in the brain that always accompanies a conscious experience, such as the scent of a rose. David Chalmers had bet against him, doubting that the dream would come true.

Years later, they realized no one could remember exactly how the bet had been formulated. It seemed impossible to declare a winner.

But I was also in Bremen in 1998. The morning after the famous pub crawl, I interviewed David Chalmers. Miraculously, I found an old cassette tape of the interview where Chalmers detailed the terms of the bet.

A clip from that ancient interview was played in the theater. The transcript scrolled across a giant screen above the stage. The conclusion was clear: Philosopher David Chalmers won the bet and received his case of wine. The audience laughed and applauded.

The gala evening in New York celebrated 25 years of progress in consciousness research – transforming from a fringe and questioned field to one nearing respectability. The mood was jubilant. A live band played a song about the soul inspired by John Lennon and the 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes.

Photo: Per Snaprud

Two Theories of Consciousness

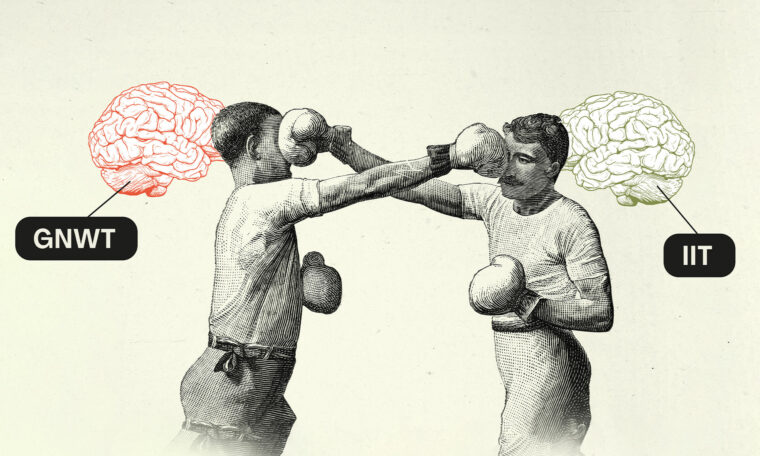

In the next segment, Liad Mudrik took the stage. She spoke about a project designed to evaluate two completely different theories of consciousness. It appeared to be a competition between two contenders.

The first is called the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory (GNWT) and posits that sensory impressions compete for space in the cerebral cortex. The most relevant signals win and are broadcast to the rest of the brain. When this happens, a conscious experience emerges. These broadcasts are handled by specific types of cells with long projections, primarily found in the frontal lobes. The theory is based on measurable properties of the brain.

The second theory, Integrated Information Theory (IIT), has a different starting point: our inner subjective world. The reasoning begins with general facts about conscious experiences – for example, that they always form a unified whole – and then describes the physical properties necessary for someone (or something) to have consciousness.

IIT is mathematically complex. A central concept is Φ (pronounced “phi”), a measure of the amount of consciousness in a brain, bacterium, computer, or any other system.

On stage in the grand theater, brand-new data from experiments designed to determine which theory aligns better with reality were presented. Positive data – aligned with a theory’s predictions – appeared in green rectangles on the screen. Negative data were shown in red rectangles.

Step by step, preliminary results from the first of several planned experiments were presented in two columns. The outcome was clear: IIT received the most green rectangles.

Photo: University of California Irvine

The Debate Escalates

This outcome irritated Megan Peters, associate professor in the Department of Cognitive Sciences at the University of California, Irvine. Sitting near the front of the auditorium, she felt the event resembled a sports competition or horse race where the goal was to reach the finish line first.

– I felt very taken aback by the use of language pitting these two theories against each other, and having one of them win, she says a year later in Tokyo.

Megan Peters criticizes Mudrik and her team for presenting new scientific results directly to the public and journalists from a theater stage without first allowing independent researchers to review them.

Moreover, she argues that the experiments conducted never seriously challenged IIT’s central components. According to Peters, it was a foregone conclusion that IIT would fare well. She believes IIT has an undeserved reputation for being a scientifically well-supported theory.

My colleagues and I published articles about the event in outlets such as The New York Times, The Economist, Nature, Science, and Forskning & Framsteg. Peters was frustrated that most reports mentioned only two theories of consciousness, whereas dozens exist with varying degrees of scientific support. She became even angrier when IIT was described as ”leading,” ”dominant,” or ”well-established.”

On platform X, she wrote: ”I am deeply disappointed in how the media has covered recent findings in consciousness science.”

Megan Peters wasn’t alone in her reaction to the portrayal of IIT as the victor during the New York gala evening. Her former mentor, Hakwan Lau, began drafting a public protest.

– This has been going on for a decade, but now it’s reached a boiling point, he says during a long interview in Tokyo.

Photo: University of Wisconsin

The first version of IIT was introduced twenty years ago by Giulio Tononi, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the USA. In recent years, one of the most prominent advocates of the theory has been Christof Koch, the neuroscientist who lost the bet about the case of wine. He is frequently interviewed about consciousness, has written four popular science books on the subject, and is a regular contributor to Scientific American.

The media marketing has included numerous exaggerated descriptions, says Hakwan Lau.

But he doesn’t place the blame solely on journalists or any single actor. Instead, he views the problems as structural.

Funding Challenges in Consciousness Research

Conducting research on consciousness is difficult. The topic lies outside the realm of what is objectively measurable. For a long time, laboratory experiments to investigate the nature of consciousness and its connection to the broader world were considered futile – work for philosophers and theologians rather than scientists. As a result, public funding agencies for scientific research have invested relatively little in consciousness studies.

Certain private foundations, however, have been more generous. These include the Templeton World Charity Foundation and Tiny Blue Dot (whose chief scientist is Christof Koch). These foundations, established by wealthy Americans with interests in subjects like ”the search for meaning, purpose, and truth” and ”expanded perception”, have provided significant funding to consciousness researchers. Thus, maintaining good relationships with billionaires is essential, according to Hakwan Lau.

– It’s all personal connections, all about what’s in the media, he says.

There is significant public interest in consciousness. According to Lau, this drives researchers to engage directly with journalists to promote their latest findings – journalists who, in turn, simplify, exaggerate, and distort the findings in their constant quest for clicks and catchy headlines. This, he argues, creates false success stories. As a result, people with control over research funding may invest in bad science, particularly in the case of IIT, according to Hakwan Lau.

Public Protest Causes a Stir

This backdrop explains Lau’s public protest. Together with his former colleague Megan Peters and a handful of like-minded researchers, he authored an open letter titled ”The integrated information theory of consciousness as pseudoscience”. It was published in a database for preliminary findings in psychological research on September 16, 2023. The letter caused an uproar.

”Civil war has broken out in the field of consciousness research”, wrote British philosopher Philip Goff on the popular science site The Conversation.

The most contentious aspect is the last word in the letter’s title, pseudoscience, which refers to something that pretends to be scientific but isn’t. Accusing someone of pseudoscience is among the gravest insults in academia.

Hakwan Lau is respected for his scientific work but also known for expressing strong opinions. If he had been the sole author, the letter might not have attracted much attention. But in the end, 124 people signed it. One of them was philosopher Daniel Dennett, who passed away earlier this year. Dennett was so influential that the organizers of the consciousness conference in Tokyo held a special evening to honor his memory with speeches and a moment of silence. Among the signatories were other prominent figures in the academic world’s invisible yet crucial system of relationships, status, and power.

One researcher who felt targeted by the letter was Giulio Tononi, the mind behind IIT. When it was published, he was on the island of San Servolo near Venice in Italy, wrapping up a seminar on his theory with about forty other researchers when cell phones began buzzing.

Accused of pseudoscience

Now in Tokyo for another seminar on the same topic (though not participating in the larger ASSC consciousness conference), Tononi reflects on the accusation.

– I could say many things. But you’re a journalist, so I won’t say much. Except to point out that some people accuse others of their own sins, he says.

David Chalmers, the winner of the bet over the case of wine, has been more vocal about the choice of words. Though not a proponent of IIT, Chalmers is an interested observer. A few days after the letter was published, he posted on X:

”IIT has many problems. But ’pseudoscience’ is like dropping a nuclear bomb over a regional dispute. It’s disproportionate, unsupported by good reasoning, and does vast collateral damage to the field far beyond IIT.”

Hakwan Lau was dismayed that the post mentioned an atomic bomb.

– You must understand that here in Japan this is not an acceptable analogy. It’s extremely insensitive, he says.

He points out that some of the letter’s signatories work at New York University, where Chalmers is a professor of philosophy.

– So, he’s referring to his junior colleague’s expression of an academic opinion as mass murdering. And that seems to me quite disproportionate, to use his own word, Lau says.

David Chalmers is one of the speakers at the Tokyo conference. When I approach him during a break with questions about his role in the conflict, he raises his arm in a defensive gesture.

– This is an extremely sensitive issue. You must understand it’s sensitive, and I won’t discuss it without careful thought, he says.

The following day, when I try again, he asks me to send written questions. One of them concerns what he has learned from the events and whether he would have done anything differently.

In an email, he describes his main role as organizer and participant during the New York gala evening:

”We had hoped that the 25 years framing would help attract some public attention to the latest science in the area. We succeeded in that perhaps a little too well”, Chalmers writes.

He believes the extensive media coverage was positive in many ways, but some articles described the tested theories as ”winners” and ”losers” instead of explaining that both have weaknesses.

”That played a role in triggering the controversy” he writes.

In hindsight, he thinks it might have been better to initially release the results more quietly rather than presenting them on a theater stage.

In his written responses, he says nothing about his post on X regarding nuclear weapons. I write to him, mentioning that Hakwan Lau believes the tweet equates the signatories of the open letter with mass murderers and that it intensified the conflict. The reply comes immediately:

”Sorry, I don’t have any comment on that.”

The Tone Risks Damaging All Consciousness Research

Philosopher David Chalmers is a central figure in consciousness research. Over a long career, he has helped make the field more respectable, contributing through influential books and philosophical papers, organizing seminars, mentoring young researchers, and fostering collaboration between philosophers and scientists. The message in his tweet is that the escalating tone now risks harming the entire field of research, not just IIT.

That concern is widespread. Liad Mudrik believes the damage has already been done. A few weeks after the open letter was published, one of her doctoral students at Tel Aviv University was set to defend her dissertation. An expert tasked with evaluating the work was a neurobiologist, not a consciousness researcher.

– His first question was: ‘Why are we talking about consciousness? We’ve just heard that it’s pseudoscience’, says Liad Mudrik.

But Hakwan Lau stands by his choice of words. Together with his co-authors, he is working on updating and expanding the open letter into a longer article for publication in a scientific journal. He explains that they have debated whether to keep the word pseudoscience in the new article.

– We voted. And the answer is yes. So, the group as a whole thinks that we should continue to use the word, says Hakwan Lau.

Kunskap baserad på vetenskap

Prenumerera på Forskning & Framsteg!

Inlogg på fof.se • Tidning • Arkiv med tidigare nummer

Exactly when the article will be published remains unclear. It will undoubtedly spark new discussions. Among the signatories is a researcher in Sweden, Renzo Lanfranco, at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. He believes the word pseudoscience should remain, perhaps not in the title but definitely further down in the forthcoming article.

The organizers of the research meeting here in Tokyo are choosing to ignore the dispute. The packed program has no room for open discussion. However, pseudoscience is, of course, a frequent topic of conversation in the corridors. Liad Mudrik brings it up in her discussion with Hakwan Lau amidst the crowd outside the underground lecture hall. The tone is respectful but far from cordial.

– What I want to convey is that when you express yourself in that way, it affects many people, says Liad Mudrik.

Hakwan Lau nods.

– I’ve thought about this, he says. There’s obviously a cost involved. At the same time, it’s important to be clear so that young researchers know what they’re getting into.

He reiterates his argument that media marketing has become more important than scientific merit in consciousness research.

– That’s what I think about when I say it’s doomed, says Hakwan Lau.

– But isn’t it more that you feel the field is moving in a problematic direction rather than being doomed? Do you see the difference? says Liad Mudrik.

– Well, the field is doomed in my opinion, Hakwan Lau replies.

– I think you should be more nuanced, says Liad Mudrik.

Hakwan Lau informs her that he has resigned from his position as a consciousness researcher.

– I’m going to quit. I don’t want to train more young researchers for this field. I don’t think it would be good for them, says Hakwan Lau.

He has accepted a new job in South Korea, where he will lead a brain imaging lab at the Institute for Basic Science, an organization funded by the Korean government. In the future, he plans to study the biology of the brain without dealing with the fuzzy concept of consciousness.

– It’s a loss for all of us, says Liad Mudrik.

– I don’t think so, says Hakwan Lau.

He glances at his watch. The conversation has lasted over half an hour. Hakwan Lau says he has an appointment to keep, excuses himself, and disappears into the crowd.

Per Snaprud

Per Snaprud is an editor at Forskning & Framsteg in Stockholm, Sweden. He is the author of Medvetandets återkomst (Return of Consciousness, Natur & Kultur 2018) and has written The Consiousness Wager for New Scientist.